- Neurosurgeon's Guide

- Posts

- The Introverts Guide To Brain Health

The Introverts Guide To Brain Health

I am so much of an introvert. I don’t get excited about social events. But even from this perspective I have a sense of how important deep social connection is. I have to work a little bit more work on it. What does loneliness mean for your health? Let’s do a deep dive.

In This Edition

The Lonliness Pandemic

Five Minute Connection

Reflections from the OR

Neuroscience of Social Interaction

“All real living is meeting.”

Why Being Lonely Might Kill You

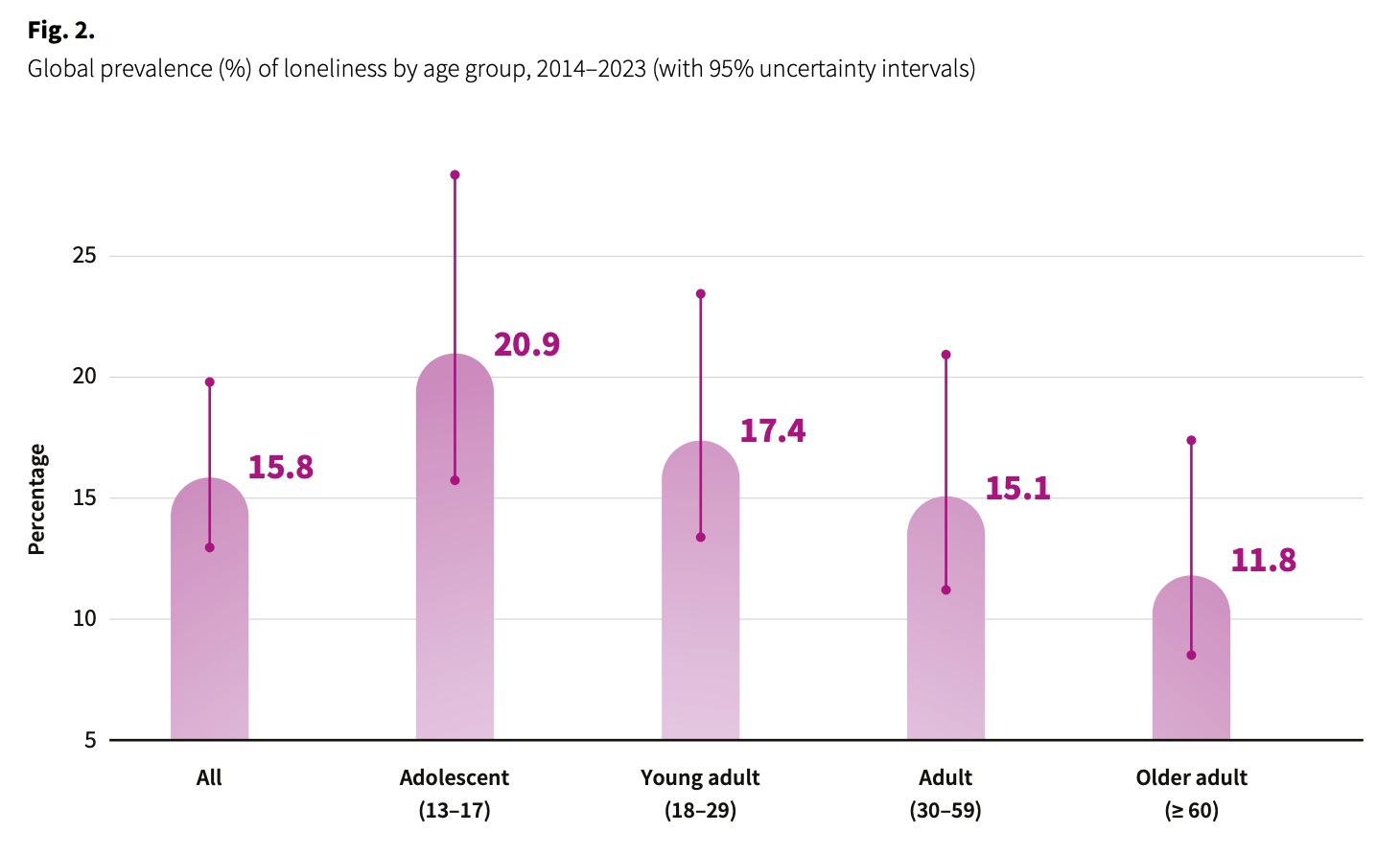

Loneliness is linked to an estimated 100 deaths every hour—more than 871 000 deaths annually.

I’ll let that sink in.

This is a rate that rivals smoking, obesity, and other well-established public health threats.

Chronic loneliness fundamentally alters brain structure and function, accelerating cognitive decline and dramatically increasing dementia risk. When we're socially isolated, key brain regions—including the hippocampus, which governs memory formation, and the prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making—begin to atrophy. The brain, evolved for social connection, interprets prolonged isolation as a threat, triggering chronic stress responses that flood neural tissue with cortisol and other inflammatory molecules.

Lonely individuals face a 50% increased risk of developing dementia, comparable to well-known risk factors like hypertension or physical inactivity. Outside the brain social isolation raises the risk of heart disease by 29% and stroke by 32%. Mental health deteriorates, with loneliness significantly elevating rates of depression, anxiety, and suicide.

Teenagers and young adults report the highest rates of loneliness, and the consequences ripple through their lives with lower academic achievement, difficulty maintaining employment, reduced lifetime earnings.

Brain Hack of the Week

Set a timer for five minutes and have one fully present conversation. Put your phone face-down (or better yet, in another room), make eye contact, and actively listen without planning your response. This could be with your partner over coffee, a colleague during a break, or even a brief call with a friend.

Social Media

@meric_mednick Check in on the men in your life. #fyp #selfimprovement #advice #lonely #helpingothers

Reflections from the OR

I hate going into an empty pre op room. Someone who has come to have a brain aneurysm fixed on spine surgery. And they are alone in the room waiting for their surgery.

"Do you have someone picking you up? Someone staying with you the first few days?"

"No, I'll manage."

"Would you like me to call anyone after the surgery? Update a family member or friend?"

"No. There's no one."

Not said with bitterness or self-pity. Just matter-of-fact. The same tone you'd use to say you don't drink coffee.

Two hours later reflexively out to the surgical waiting area. But of course there’s no one there. I stand there longer than I need to. Then I went back to recovery and told her. She was still groggy, barely tracking, but she nodded. "Thank you, doctor." No hand to hold. No tears of relief. Just her, waking up alone from brain surgery.

We need each other.

Social interaction is one of the most powerful rewards your brain can experience, activating the same dopaminergic circuits in the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens that respond to food, money, and other primary rewards.

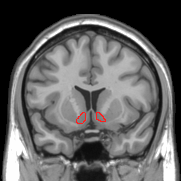

Look At Those Cute Nucleus Accubens

When you engage in social interaction, oxytocin neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of your hypothalamus fire rapidly, releasing oxytocin into the ventral tegmental area—a key node in the brain's reward circuitry.

This isn't just about feeling good. The oxytocin-dopamine interplay fundamentally shapes brain networks involved in social cognition, emotional regulation, and memory formation. These neural systems work together across the prefrontal cortex, insula, amygdala, and hippocampus, creating what neuroscientists call the "social brain network."

When this system functions well, it builds cognitive reserve. Your brain's resilience against aging and disease. When it's chronically deprived through isolation, the consequences cascade: the amygdala becomes hyperactive, perceiving threats everywhere; stress hormones flood the hippocampus, accelerating memory decline; and the prefrontal cortex atrophies, impairing decision-making.

The elegant design reveals an evolutionary truth: our brains didn't evolve for solitude. They're fundamentally social organs, wired through millions of years of natural selection to seek, maintain, and thrive within human connection.

Stay sharp,

Colin