Neurosurgeons (at least some) understand that the most dangerous moment in the operating room isn't uncertainty, but false certainty, and the same principle applies to how we think, decide, and learn in everyday life. Your brain's greatest strength isn't knowing everything—it's knowing when you're wrong.

In This Edition

Your Brain Misremembering

Brain Hack of the Week

Reflections from the OR

The Neuroscience of Memory

In surgery, as in life, the problem is not to make the right decision. The problem is to know when you are making the wrong one.

Why Misremembering Isn’t A Glitch

Every time you remember something you aren’t playing back a recording; you’re reconstructing an event. Basically piecing together fragments, filling gaps with assumptions, and inadvertently weaving in details that never happened. Your brain is actively rebuilding the past every time you access it.

Memory is susceptible to misattribution, where specific memories bind to the wrong moment, location, or subject. That argument you had last week? You might remember your partner saying something they never said. That childhood birthday party? Some of those "vivid" details might be from photographs you've seen, not the actual event. We tend to place past events into existing mental schemas to make memories more coherent, often at the expense of accuracy.

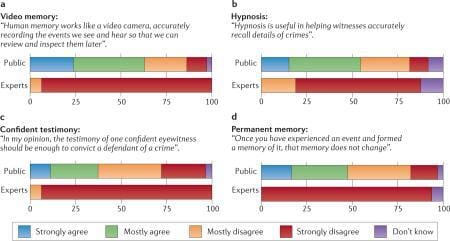

What we think of our memory

And we don’t have great insight as our brain works like this. Participants who falsely remembered seeing broken glass in an accident were just as confident as those who remembered actual details. The certainty you feel when you say "I know exactly what happened" is simply your brain's assessment of how well the pieces fit together, not a measure of truth. It is posthoc.

The brain works like this probably because familiarity is usually an excellent cue that something happened before. But it means we need intellectual humility about our own recollections. The most dangerous moment isn't when you're uncertain about a memory. It's when you're absolutely sure you're right, but you're reconstructing rather than remembering. In those moments, conviction becomes the enemy of truth, and humility ("I might have this wrong") becomes the only honest position.

Retrieval Practice

Re-reading feels productive but creates "fluency illusions" i.e. you think you know it because it looks familiar. Retrieval practice feels harder because it is harder, and that difficulty is what makes memories stick.

Instead:

After reading a chapter: close it and summarize the key points from memory

Studying for an exam: test yourself repeatedly instead of rereading highlights

Learning a new skill: explain it to someone (or to yourself) without notes

Why It Works:

Each time you successfully pull information from memory, you strengthen that neural pathway

The effort of retrieval creates stronger, more accessible memories than passive review

You're literally rewiring your brain to make that information easier to access later

Reflections from the OR

I can't remember my first EVD; little tubes we slip into patient’s brains often to relieve pressure..

“What was it like?” I have nothing. I know it happened during my first month of residency. I know the chief resident was probably standing right there. I'm sure my hands shook. But the actual moment? Gone.

What I do remember, with painful clarity, is my fifth or sixth. The one where I couldn't hit the ventricle Where I tried twice, then had to step back while the attending took over. The patient was fine.. But I can still feel the heat in my face, the weight of everyone watching.

Funny how that works. The success that should have been a milestone doesn’t stick but the minor failure that meant nothing in the grand scheme sticks.

I see this with patients too. They'll forget entire conversations we had about their diagnosis, the treatment plan, the prognosis. But they'll remember exactly how the nurse looked at them when delivering bad news. Or that I was eating a granola bar when I came to check on them post-op.

We don't remember what happened. We remember what felt important.

Maybe that's why teaching is so hard. I can explain a procedure perfectly, and they'll forget it by morning. But if I tell them about the time I screwed it up? That sticks.

The Neuroscience of Memory

Memory formation follows three distinct stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Unlike a camera recording to a hard drive, your brain actively constructs each memory.

The hippocampus, located in the medial temporal lobe, serves as memory's command center, converting fleeting short-term experiences into lasting long-term memories. Think of it as a neural switchboard, rapidly forming associations between the sights, sounds, and emotions of a moment. These associations are gradually stabilized within distributed neocortical circuits through close interactions between the hippocampus and neocortex in a consolidative process.

The amygdala tags emotionally charged experiences, making them stickier in memory. This explains why you vividly remember your first kiss or a near-miss car accident, but forget what you had for lunch last Tuesday.

At the cellular level, memory depends on the brain's ability to rewire itself. Long-term potentiation strengthens connections between neurons based on experience, primarily in the hippocampus, enabling the brain to encode new information. The more you activate a neural pathway, the stronger it becomes. This is the essence of learning.

Perhaps most fascinating is how memories are reconstructed rather than simply retrieved, with the same neural circuits supporting both recall and imagination. After encoding, not all memories share the same fate—some are forgotten while others persist, often in transformed form. Your brain actively decides what's worth keeping, consolidating critical experiences while letting trivial details fade away.

Understanding these mechanisms isn't just academic—it illuminates why memory fails, how disorders like Alzheimer's attack the system, and ultimately, what makes you, you.

Stay sharp,

Colin